by O’Brien Brown

Early in the morning of July 1, 1916, a mist blanketed the lolling hills of the Somme region of northwestern France. Larks flittered and sang in the air as the haze burned off to reveal a brilliant summer’s day. On the British side of the front lines, crimson poppies and yellow grass swayed in a slight breeze. Across the wire, however, the earth heaved and shook as artillery shells slammed into the German trenches. The barrage rose to a shrieking fury as British troops, gathered in their jumping-off trenches, pressed into the chalky earth awaiting the shrill whistles of their officers telling them to go over the top.

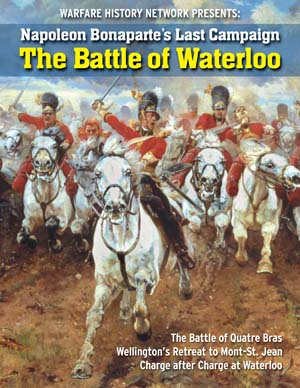

Gain new insight into the battle that brought the end of Napoleon’s rule in France.

Get your copy of Warfare History Network’s FREE Special Report,

The Battle of Waterloo

At 7:30, the devastating barrage lifted as British officers, eyes on their watches, blew their whistles and the men crawled up ladders, walking shoulder to shoulder into No Man’s Land. After a few yards, undamaged German machine guns opened up, catching the neat rows of slowly moving troops by surprise as they attempted to weave through the barbed wire emplacements, cutting them down in droves. “I am staring at a sunlit picture of Hell,” observed 2nd Lt. Siegfried Sassoon as he watched the attack unfold. Within a few hours 60,000 men had fallen, 20,000 never to rise again, in the worst single day of action in British military history. [To put this in some perspective, the Allies on D-Day 1944 attacked with 170,000 airborne and infantry, suffering 10,000 casualties, of which 4,000 were deaths; on America’s bloodiest battle day, the Battle of Antietam, 4,700 soldiers died.]

A Gruesome Beginning

This was the first day of the Battle of the Somme, a bloody, protracted struggle that was to become seared into the minds of succeeding British generations as the place where youth and innocence were slaughtered, a gaping wound that mars the national conscience to this day.

This appalling opening day was not due to a lack of planning. Indeed, few battles of the Great War were so well thought out and minutely organized as this. The plan of attack had originated at the Chantilly Conference in December 1915 where Allied commanders from France, Great Britain, Russia, Serbia, and Italy had met to coordinate strategy for the coming year, developing a grand scheme envisioning Russian and Italian offensives along their respective fronts. The decisive thrust, however, would occur in the west. Accordingly, French Commander-in-Chief General Joseph Joffre requested that the British Expeditionary Force, led by their new commander General Sir Douglas Haig, hit the enemy with 25 divisions on a 14-mile front with a simultaneous French assault consisting of 40 divisions along a front stretching 25 miles from the Somme to Lasigny. The battle was tentatively set for the summer, with Joffre thinking of July 1.

The choice of the Somme region as a center of operations was questionable—an observation made easy by hindsight. It is an area of ravines and rises, forests, muddy riverbanks, and soft rolling land—fine for farming and summer strolls, murderous for attacking infantry. The Germans occupied all of the high ground and had built deep, well-constructed dugouts sometimes extending more than 40 feet into the chalky ground. Beyond the German lines, there were no vital points or clear objectives to justify a major assault. But on the map this was where the British and French Armies touched, and for military minds this seemed like a logical place for a joint offensive. It was also “clean country,” uncluttered and unscarred by previous battles. Strategically, for the French a fight here would keep the focus of the war on the Western Front where, they believed, the war would be won or lost. And for Joffre personally, it was expedient to have the attacking forces under his command, on his front. A wise and wily old man, he wished to ensure that his Anglo-Saxon allies fully involved themselves in the fighting.

Although Haig had wanted his armies to strike at the Germans in Flanders, he demurred to General Joffre, the de facto generalissimo of the Allied forces, and threw himself into the planning for the attack with enthusiasm. To understand the character of the Somme battles, one must understand its driving force, Haig. An excellent military technician and planner, he was a man who unfortunately combined unbounded optimism and self-confidence with obstinacy. Throughout his career, his meticulously planned campaigns tended to be orthodox and, many have argued, unimaginative. An undistinguished student at Camberley Staff College, he did, however, possess a fine political nose; he married a lady-in-waiting of the royal family, thus establishing vital connections with King George V that assisted him greatly. Indeed, Haig, a cavalry officer, had risen rapidly through the ranks and had been appointed C-in-C of the BEF due in part to his secret channel to the king, which he ruthlessly used to undermine his predecessor, General Sir John French, removed from command in 1915. An odd man, reserved, urbane, and deeply religious, Haig displayed little concern for the suffering of his troops and great loyalty to his field commanders while gradually becoming convinced that God had singled him out for some divine role. Vilified by many, defended by few, he is today considered one of the most controversial commanders of a war in which the reputations of top commanders have been harshly judged by later generations.

1 Million Germans, 500,000 French Defenders

While the Allies made their offensive plans for the coming year, the Germans were not idly resting in their trenches. Believing Britain to be Germany’s main enemy, Chief of Staff General Erich von Falkenhayn conceived a macabre plan to “compel the French General Staff to throw in every man they have” into a battle of attrition at the militarily insignificant series of forts located at Verdun. Once the French had been destroyed, reasoned Falkenhayn, Germany could then concentrate her might on crushing Britain. Accordingly, on February 21, after a short, brutal artillery bombardment, one million German soldiers dashed against approximately 500,000 French defenders, beginning the longest, bloodiest battle in history. By May the French had lost 133,000 men and had 42 divisions engaged in fierce fighting at Verdun. Joffre now expected Haig to take on more responsibility for the upcoming Somme offensive.

The Somme became a British show. Haig’s spearhead would be the newly created Fourth Army, 20 divisions strong, commanded by Lt. Gen. Sir Henry Rawlinson, an experienced and thoughtful infantryman, supported by the Third Army under General Edmund Allenby, which had taken over part of the old French line north of the River Somme in 1915.

Haig and Rawlinson’s fighting forces were relatively new material. The old, small, highly professional army of 1914 had been largely destroyed by 1916, wiped out trying to halt the German onslaught at the beginning of the war. The “New Army” or “Kitchener’s Army” was almost entirely made up of volunteers, men who had patriotically answered Secretary of State for War Lord Kitchener’s call for more soldiers. British men had joined up in the millions, resulting in the creation of five new armies, consisting of six divisions each. Of the 13 divisions for the initial attack at the Somme, only four were regular army units. The rest were New Army men, untried, untested, unbloodied, soon to be thrown against the seasoned professionals of the Imperial German Army. These armies were socially stratified, with officers emanating largely from the south and west and the affluent large cities, while the lower ranks of former farmers, miners, ship builders, etc., came from villages and other rural regions of Britain. “Thus there came about,” writes John Keegan, “a meeting of strangers.” Indeed, regional accents were so strong as to almost make verbal communication mutually unintelligible. On top of this, the infrastructure of the New Armies had not been developed sufficiently to train the masses of fresh officers and men. Uniforms and equipment were lacking, and the men spent endless hours on the drill grounds instead of learning to handle their weapons. Many units were understaffed, their officers overworked, hastily trained and as young and inexperienced as the men they had to lead.

Jacob’s Ladder, Lulu Lane And Pottage Trench

The vast majority of these men, enthused with an almost religious feeling of patriotism and a naïve belief in their leaders, enlisted in “Pals” or “Chums” regiments. Arising from Victorian society’s penchant for clubs and associations—sports, church, craft guilds—entire company staffs or rugby club members, for instance, would join up with the promise that they could train and serve together. Although given official designations, the units of this truly unique citizen’s army were often simply known as “the Leeds Pals,” “Grimsby Chums,” “the Manchester Commercials,” and so forth.

These fresh troops, innocent to war, took up their positions on the Somme, a “quiet sector” of the Western Front where little fighting had taken place since 1914 and the troops had adopted a “live and let live” system. Because of this, the men had the “luxury” of being able to build proper trench systems. Defended by belts of barbed wire snarling all passages through No Man’s Land, the trench itself ideally consisted of a parapet (the side facing the enemy), often sand-bagged, a parados (the rear of the trench), and a fire-step which soldiers shot from. The men gave the trenches names, often humorous, such as Jacob’s Ladder, Lulu Lane, Pottage Trench. A “perisher”—soldier’s slang for a periscope—peeked over the lip of the trench, allowing a view of the enemy. Sometimes the trench sides were supported by wood paneling, wickerwork, or wire mesh, the floor laid with wooden duck boards—ladder-like constructions designed to keep soldiers’ feet out of the mud, a near impossibility given the wet climate. Enterprising men dug cubbyholes for sleeping and protection into the trench wall; the deep dugouts so beloved by the Germans were not constructed because the Allies never intended to stay in the front lines for very long. Two hundred yards or so behind the front line was the support line, with a reserve trench perhaps another 400 yards beyond this. All were connected by communication trenches and all were “traversed” or zigzagged to prevent a shell blast or attacking troops from causing destruction down the whole length of the line. Here the men received their rations—either tinned bully beef, tea and jam, or a hot greasy stew prepared in vast cookers behind the lines and brought up by men detailed for this duty, and a rum or wine ration. This whole network, however, was rapidly reduced to a gooey mess of mud, collapsed walls, smashed equipment, and rotting body parts by the effects of shelling and the weather. Refuse, rats, and black clouds of flies were rampant.

Although often only a few yards separated the opposing trench lines, soldiers normally got only a fleeting glimpse of the enemy. “Sometimes in the valley on the right,” wrote Guy Patterson, an officer with the 13th Battalion, Royal Welsh Fusiliers, “a grey shadow would stand for a few seconds, and then slide from sight, like a water-rat into his hole. At these we fired.” The only enemy soldiers the men really saw were either prisoners or dead.

Hand-to-Hand Fighting was Quick and Deadly

Trench life was usually one of dull routine. But some of the most vicious and terrifying fighting of the war took place during nighttime raids, carried out to capture enemy soldiers for intelligence purposes, to assess damage inflected by shelling, to keep the enemy tense, and to ensure that the troops kept their fighting edge. Brief, violent raids involving sometimes a handful, other times hundreds of men, were hated and dreaded. Although well armed with grenades, pistols, and light machine guns, many soldiers fashioned their own weapons for such operations: long jagged daggers, clubs, maces with nails driven into their heads, brass knuckles. Once a raiding party cut a path through the wire, the men pounced on the unaware enemy in his trenches where hand-to-hand fighting was quick and deadly; those overwhelmed rapidly surrendered, while the rest simply ran away behind the nearest traverse. Here the real trench fighting occurred—not the bayonet thrusts of fanciful imagination, but “bombing” each other with hand grenades. After rounding up the prisoners and anything that could be of use to the intelligence units, the raiding party then had to make its way back to the lines, only this time with the enemy fully alerted and waiting with flares, machine guns, and even artillery support, called in by telephone.

If no fighting was going on, units were rotated out of the line to the relatively peaceful back areas where they were entertained by prostitutes, enjoyed local foods such as fried eggs with French fries, and forgot the war for a while with a bottle of strong beer or wine. Many of the regular ranks—men from the lower classes—had never been so well fed and cared for in their lives.

With the multitudinous raw material of the New Armies, Haig and Rawlinson developed a battle plan that envisioned obliterating the Germans with a massive week-long artillery bombardment meant to pulverize their defenses, knocking out batteries and machine-gun nests, destroying trench systems, and ripping huge gaps in their barbed wire entanglements. Walking through the chopped up wire, British soldiers would take possession of the ruined, empty trenches. The main attack, occurring on an 18-mile front, would follow closely behind a carefully orchestrated “creeping barrage” that would screen their advance, stunning or killing their opponents in the first line of trenches before lifting on to the second line and beyond.

The objectives were to capture the ridges around the village of Pozières—the high ground from which the Germans could observe the important British base at Albert—eliminate enemy artillery and machine-gun positions concealed in Delville and High Woods at its crest, and establish British troops between the village of Serre and the River Ancre. Once the German lines had been breached, Haig planned to send the cavalry through in a giant wheel to the north to “roll up” the German forces, crushing them against the Belgian coast. Ultimately, the British were to break out into open country, and perhaps even end the war.

Rawlison and His Staff Prepared for “The Big Push”

Before that occurred, Haig wished to smash through to the village of Bapaume, several miles behind the German lines. Rawlinson, however, was more realistic, believing that his soldiers should advance in stages, tearing off chunks of the German line piece by piece and securing the high ground for future operations. He did not think a breakthrough was possible. Meanwhile, French Northern Army Group commander General Ferdinand Foch made plans with General Marie Fayolle’s Sixth Army to strike the German lines to the south of the River Somme along an eight-mile front. His force, though, had been pared down to a mere three divisions because of the drain on French manpower caused by the brutal fighting at Verdun.

Before that occurred, Haig wished to smash through to the village of Bapaume, several miles behind the German lines. Rawlinson, however, was more realistic, believing that his soldiers should advance in stages, tearing off chunks of the German line piece by piece and securing the high ground for future operations. He did not think a breakthrough was possible. Meanwhile, French Northern Army Group commander General Ferdinand Foch made plans with General Marie Fayolle’s Sixth Army to strike the German lines to the south of the River Somme along an eight-mile front. His force, though, had been pared down to a mere three divisions because of the drain on French manpower caused by the brutal fighting at Verdun.

Rawlinson and his staff worked out the finer details of “the Big Push,” as the approaching battle was called, aiming to hit the Germans near the village of Mametz, push on to Pozières at the top of the ridge, then cut eastward to enfilade the secondary German trenches. An attack at Beaumont Hamel to the north would hold up enemy forces while a feint at the village of Gommecourt by the Third Army was to confuse the enemy into thinking the main attack was there. The French would advance toward the town of Péronne. For much of the assault, Rawlinson’s men would have to attack a well-defended, dug-in enemy—uphill.

All of Haig’s organizational talents were evident in the buildup to the Big Push. In the weeks before the attack, army engineers and working crews were busy building roads and laying railway lines, digging jumping-off trenches and artillery emplacements and stockpiling nearly three million shells at massive dumps. Field hospitals were set up, graves dug, latrines laid out, water pumps built. The preliminary artillery barrage would consist of more than 1,500 guns of all sizes slinging over 1.7 million shells into the German lines. A special surprise feature was being dug by the Royal Engineers. Working by night, diggers scooped mines out of the chalky earth, deep under various German positions along their lines, filled with tons of explosives and wired to be set off on “Z” day, or zero hour. This was an eminently practical use of force because the British would essentially be attacking a fortress and the techniques of siege warfare were called for.

The smallest details were thought out. Captain R.J. Trousdell of the Royal Irish Fusiliers later recalled that the men carried, along with their newly issued steel helmets, rifle, gas masks, ammunition pouches, and bayonet, “two days rations, bomb, pick or shovel, Ayston fans (for clearing gas out of dugouts), flags for showing our position to Artillery, Verey lights, and on each man’s back was fitted a triangular piece of tin in order to show the position of our advanced line to aeroplanes” and other assorted equipment such as rolls of barbed wire and empty sandbags for consolidating newly won ground. The territory to be attacked was studied, and the troops carefully rehearsed the advance with some units even constructing clay scale models of the field in order to plan their movements down to the last detail. Aerial photographs were also of great assistance. In the days before the assault, special parties went out to the jumping-off positions, laying white tape down so that the troops could find their starting positions. Some officers, such as Siegfried Sassoon, crawled out into No Man’s Land on their own initiative and personally snipped gaps in the barbed wire. “I was cutting the wire by daylight,” he later wrote in his memoirs, “because common sense warned me that the lives of several hundred soldiers might depend on it being done properly.”

“The Men Must Learn to Obey by Instinct Without Thinking”

The French battle plan differed from that of their allies. Drawing on their experience gained through hard fighting since the beginning of the war and at Verdun, the French planned to use 900 heavy artillery pieces to smash up the German trenches, to be unleashed in a brief, violent preliminary barrage to gain surprise. More importantly, highly trained French troops were to advance in small groups, worming along the contours of the ground and moving up on the enemy in short rushes, thus presenting any surviving opponents difficult targets to aim at. They, too, would attack behind “creeping barrage” fire at which they were better because of experience gained in the field and intensive training. They pushed for 7:30 as zero hour to give the artillery maximum visibility, even while surrendering the basic principle of attacking at dawn.

Because the men and officers of the New Armies were for the most part inchoate, Haig and his generals believed they should attack with fixed bayonets in well-ordered waves, each succeeding wave of upright men pushing on the backs of those in front at one-minute intervals, their momentum sweeping the Germans in front of them. “The men must learn to obey by instinct without thinking,” ran the “Red Book,” the Fourth Army’s training manual. “The whole advance must be carried out as a drill.” Covering fire was not given great importance because it had been calculated that the German infantry and artillery would not survive the thunderous artillery barrage. Those who did survive would lose the “race” to their parapets, which the British infantry was expected to win. “You will find the Germans all dead,” the Newcastle Commercials were told by their officers.

Since the beginning of the fighting at Verdun, Falkenhayn had been telling his commanders along the line to expect an Allied relief attack. Because reserves were sparse, thanks to Verdun, he wanted the front lines well defended, which resulted in the troops expending great efforts to make their defensive works as strong as possible. Since aerial photography indicated the buildup of supply dumps and the construction of roads and railways in the Somme region, General Fritz von Below, commander of the 16-division strong Second Army, felt that an offensive was imminent, although Falkenhayn long thought it would occur farther to the north.

The German Army on the Somme proudly occupied ground captured in the early days of the war. Experienced “old sweats” from 1914, believing strongly in both their cause and their leaders, fully intended to keep and hopefully increase conquered territory. Their deep dugouts, complete with furniture and provisions and large enough to accommodate an entire company, provided a psychological sense of security. Conquered villages had been turned into mini-fortresses, armed with machine guns and mortars. In front of their trenches thick belts of well-laid wire gave added security. About a thousand machine-gun emplacements, many reinforced with concrete, bristled from concealed locations. The men had been trained to sit out an enemy bombardment in their dugouts and then to rush out the moment it stopped to man the parapets and repel an attack. They, too, would be in a race for their lives. They realized that their existence depended on reaching their positions before the enemy had time to cross No Man’s Land and cut his way through the wire. They would fight hard and determinedly.

One Week Before Z-Day

In the meantime, on June 4 the Russians attacked in Galicia. Known as the Brussilov Offensive, 600,000 Russian troops struck at a similar number of Austro-Hungarian forces, capturing and killing huge numbers of them. Falkenhayn was forced to dispatch five sorely needed divisions to counter this major threat to Germany’s ally. Because of an Austro-Hungarian attack in the Trentino, Italy’s planned offensive in the Isonzo sector did not get under way until August 6, when it enjoyed initial success but at a high cost in men.

On June 24, one week before Z-day, the British began their artillery bombardment to destroy German guns, wire entanglements, and front line troops, opening shots for what one historian has described as “the longest concentrated artillery bombardment in modern warfare.” What they surrendered in tactical surprise they felt they would gain through the brutal, crushing weight of 18-pounders, 4.5-inch howitzers, 60-pounders, and trench mortars. Heavy howitzers were used for counter-battery work, to knock out communication trenches and to disrupt the movement of reserves and materiel.

The Germans sat ensconced in their deep dugouts, listening with terror to the din of crashing shells above their heads. Many were entombed by direct hits and died of suffocation. Trench walls collapsed, the soldiers manning them blown to bloody hunks of flesh or traumatized with shell shock. Whenever the shelling ceased, the men rushed up from their dugouts to man the parapets, only to be caught once the guns began firing again, forcing them into their subterranean holds once more.

Yet despite the tremendous damage done, disturbing reports were coming in to many British battalion headquarters on the eve of the attack. Parties sent out to check for gaps in the wire found that huge sections had not been destroyed. The trouble was that the 18-pounder batteries, assigned the task of cutting the wire, fired shrapnel shells with a slow fuse that exploded high above or under the wire, tossing it into impenetrable knots or bursting harmlessly above, but not slicing through. An appalling number were duds, thanks to scandalously poor workmanship. Furthermore, in spite of the magnitude of the barrage, there were too few heavy guns firing, and these had been spread out too thinly. Many of the gun crews were badly trained, with accuracy not considered of vital importance. Thus, although the bombardment was a miserable thing to live through, the majority of German troops survived it with their wire, machine guns, and artillery in good condition even while the trench systems themselves had been devastated. For them, once the battle started the race was nearly won—they would merely have to run out of their dugouts, man their parapets, and fire into the oncoming enemy. In many ways, the attack as planned was already doomed to failure.

Z-Hour Approaches

But the vast majority of British troops had no inkling of this. Those in the attacking battalions had for the most part been billeted in villages or other areas behind the lines. Originally set for June 29, the attack was postponed until July 1 because of bad weather. As Z-hour approached, the men tramped along communication trenches, being issued ammunition, extra rations, grenades, and even pigeons in wicker cages for communication. As they took up positions at their jumping-off points, some prayed, others penned letters home, but most awaited the first battle in their young lives in thoughtful silence. Virtually all, though, were heartened by the tremendous pounding of their guns, believing that the coming assault would be a “walkover” to take possession of empty trenches. “There was a wonderful air of cheery expectancy over the troops,” recalled Major H.F. Bidder of the Royal Sussex Regiment. “They were in the highest spirits, and full of confidence. I have never known quite the same universal feeling of cheerful eagerness.”

July 1 dawned in an eerie white mist with a light rain falling, soon to vanish into a blazingly sunny day. For most a hot breakfast arrived from the rear and the men ate as their officers went through their orders, brushed off their uniforms, and grabbed hold of their walking sticks, a few even carrying swords: the British officer at this time was expected to lead, care for, and instruct his men, not kill. At around 6:30 in the morning the drumfire heightened to a roaring crescendo as nearly every gun and mortar opened up along the line, the shells raining down at a rate of 3,500 per minute onto the German positions. “Fifteen-inch howitzer and 9.2 shells were falling in Gommecourt Wood,” recalled a solider in the Queen Victoria’s Rifles, “whole trees were uprooted and flung into the air, and eventually the wood was in flames. The landscape seemed to be blotted out by drifting smoke.” As Royal Engineers placed their hands on their plungers to blow the mines, infantry officers nervously kept their eyes on their synchronized watches, awaiting zero hour. Now the troops were issued “liquid courage”—strong navy rum, to steel and calm nerves and give them a jolt of fire. But one soldier remembered passing by men in the front lines, “staring like persons in a trance across No Man’s Land, their powers of action apparently suspended.” Two hundred British battalions—100,000 men—would attack that day.

Mines Blew a Hole 90 ft. Deep and 300 ft. Wide in the German Lines

A few minutes minus zero, mammoth mines at Beaumont Hamel, La Boiselle, and other locations went off, sending tons of earth and men tumbling into the sky. One mine—the largest on the Western Front and now known as the Lochnager Crater—was made up of 60,000 pounds of guncotton and blew a hole 90 feet deep and 300 feet wide in the German lines. Then there was a moment of silence as all the guns ceased firing. At 7:30, the officers blew their whistles, scrambled up ladders and out into No Man’s Land, walking sticks probing the ground in front of them, their men following as rehearsed behind, forming up in lines, one wave behind the other. From the 8th East Surreys, a football kicked high in the air announced their advance. Major Bidder recalled how “the moment came, and they were all walking over the top, as steadily as on parade, the tin discs on their backs … glittering in the sun.” The commander of the 9th Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers related how his men calmly went over the top: “Here and there a boy would wave his hand to me as I shouted good luck.… And all had a cheery face. Most were carrying loads. Fancy advancing against heavy fire with a big roll of barbed wire on your shoulder!” The artillery was now slamming into the enemy’s support trenches to avoid hitting their own men as they moved forward.

A few minutes minus zero, mammoth mines at Beaumont Hamel, La Boiselle, and other locations went off, sending tons of earth and men tumbling into the sky. One mine—the largest on the Western Front and now known as the Lochnager Crater—was made up of 60,000 pounds of guncotton and blew a hole 90 feet deep and 300 feet wide in the German lines. Then there was a moment of silence as all the guns ceased firing. At 7:30, the officers blew their whistles, scrambled up ladders and out into No Man’s Land, walking sticks probing the ground in front of them, their men following as rehearsed behind, forming up in lines, one wave behind the other. From the 8th East Surreys, a football kicked high in the air announced their advance. Major Bidder recalled how “the moment came, and they were all walking over the top, as steadily as on parade, the tin discs on their backs … glittering in the sun.” The commander of the 9th Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers related how his men calmly went over the top: “Here and there a boy would wave his hand to me as I shouted good luck.… And all had a cheery face. Most were carrying loads. Fancy advancing against heavy fire with a big roll of barbed wire on your shoulder!” The artillery was now slamming into the enemy’s support trenches to avoid hitting their own men as they moved forward.

As soon as the bombardment lifted, the surviving German troops raced out from their holes in the earth, eyes blinking in the radiant sunlight, hearts pumping from the rush and terror of battle. Rapidly they lined the shattered remnants of their trenches, set up their machine guns, and looked in horrified wonder at the slow-moving lines of khaki approaching, their rifles sloped forward, bayonets catching the sunlight. The Germans sighted down the barrels of their Mauser rifles and Maxim machine guns, letting the British come into range. F.L. Cassell, a German soldier, remembered “the shout of the sentry, ‘They are coming,’ … Helmet, belt and rifle and up the steps … there they come, the khaki-yellows, they are not twenty metres in front of our trench. They advance slowly, fully equipped … machine-gun fire tears holes in their ranks.”

The British soldiers approached the wire which they were convinced would be cut to shreds. It was not. The guns, remembered Corporal W.H. Shaw of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers, “hadn’t made any impact on those barbed-wire entanglements. The result was we never got anywhere near the Germans. Never got anywhere near them. Our lads was mown down. They were just simply slaughtered.” It was almost surreal, a midsummer’s stroll into death. At many places, the troops had to first pass through their own wire where they were wiped out by enemy machine-gunners.

“For some reason nothing seemed to happen at first,” remembered Private W. Slater of the 2nd Bradford Pals. “We strolled along as though walking in a park. Then, suddenly, we were in the midst of a storm of machine gun bullets and I saw men beginning to twirl around and fall in all kinds of curious ways as they were hit.” German artillery and machine guns were firing now, simply traversing along the slow-moving lines, and the British dropped in neat rows as they advanced. An officer who visited the field later reported “line after line of dead men laying where they had fallen.” In some places where gaps in the wire had been located, the troops were forced to line up to file through, and were easily chopped down. After having been bombarded for a week, the Germans eagerly blasted away at them, working the bolts of their rifles as fast as they could, some even rising up above the parapets to take pot shots at the clumped masses of enemy. “We had lain for seven days under the drum-fire,” recalled Unteroffizier Paul Scheytt, 109th Reserve Regiment, “… now we’d pay them back in their own kind.”

2 Years in the Making; 10 Minutes To Destroy

The slaughter was astounding: The 8th Division lost 5,274 men out of 8,500 and 218 officers from 300 in less than two hours; at Fricourt the 10th West Yorkshire and the 7th Green Howard Battalions were wiped out; the 810 men of the Newfoundland Regiment, attacking “Y” Ravine near Beaumont-Hamel, left 710 dead and wounded on the field in the space of a few minutes. A signaler from the Accrington Pals, still in the trenches, was “able to see our comrades move forward in an attempt to cross No-Man’s Land, only to be mown down like meadow grass.” The British forces had lost the race. “We were two years in the making,” recalled Private A. Pearson who served with the Leeds Pals, “and ten minutes in the destroying.”

The slaughter was astounding: The 8th Division lost 5,274 men out of 8,500 and 218 officers from 300 in less than two hours; at Fricourt the 10th West Yorkshire and the 7th Green Howard Battalions were wiped out; the 810 men of the Newfoundland Regiment, attacking “Y” Ravine near Beaumont-Hamel, left 710 dead and wounded on the field in the space of a few minutes. A signaler from the Accrington Pals, still in the trenches, was “able to see our comrades move forward in an attempt to cross No-Man’s Land, only to be mown down like meadow grass.” The British forces had lost the race. “We were two years in the making,” recalled Private A. Pearson who served with the Leeds Pals, “and ten minutes in the destroying.”

Miraculously, troops on the Fourth Army’s right pressed on to their objectives and took the German front lines. The Leipzig Redoubt, a German strongpoint, fell and the village of Montauban was captured. The village of Mametz was overrun as well, but only after 159 Devonshire Regiment soldiers were killed by a lone German machine gun, situated a mere 400 yards away. Another successful attack occurred at the village of Serre, reached by the 6th Royal Warwicks who retreated to their starting lines after losing 520 killed, 316 wounded from their original attacking force of 836. By the end of this grim and awful day, 20,000 Britons lay dead and 25,000 had serious wounds. Some battalions no longer existed; a fifth of the entire attacking force was gone. The Germans had only lost about 6,000 men. The diversionary attack at Gommecourt had gone badly as well, with two divisions losing 7,000 men.

One bright spot on this day was the French effort, which achieved all of its objectives, except the taking of Péronne, with 7,000 casualties. Their tactics—learned on the shattered battlefields of Verdun—had proven superior. By concentrating heavy artillery on certain points on the German lines, and by opening their attack with a short, intense bombardment, the French had destroyed the wire and won tactical surprise. When their troops went over the top, they did not advance in parade lines, but in small groups, rushing forward from crater to crater, finally overrunning the German positions. They took 3,000 prisoners and 80 artillery pieces. As the attack on the Somme occurred during the 132nd day of the Battle of Verdun, this was both an admirable triumph for French tactics and training, and also belies the old myth that the French Army was near collapse.

Another positive feature was that the Allies enjoyed almost complete air superiority. French and British aircraft together put up 386 machines against Germany’s 129, a three-to-one ratio. The sleek and maneuverable French Nieuport fighter completely outclassed the German monoplane Fokker E-class aircraft. Although the Royal Flying Corps was hampered by inadequately trained crews and obsolete designs, such as the DH2 fighter and the BE2 observation craft, it aggressively bombed German supply dumps and railroad lines, and harried the infantry with strafing missions. During the first four days of the attack, RFC bombers dropped 13,000 bombs. But the price was so high—the corps lost 20 percent of its forces within a few days—that the RFC had great difficulties finding replacements, and the life span of air crews was measured in weeks.

A Public Stunned by the List of Soldiers Killed, Wounded, and Missing

Back on the ground, roll call became a perverse and sad ceremony for the Third and Fourth Armies on the evening of July 1. In the 14th Platoon of the 1st Rifle Brigade, for example, only one man was left out of the original 40. On the home front, however, the population was not told the truth, with newspaper headlines announcing “Kitchener’s Boys—New Armies Make Good,” or “Great Day on the Somme.” But these same newspapers also began publishing the lists of the killed, missing, and wounded. The public was stunned and horrified, especially those towns that had raised “Chums” or “Pals” battalions.

Back on the ground, roll call became a perverse and sad ceremony for the Third and Fourth Armies on the evening of July 1. In the 14th Platoon of the 1st Rifle Brigade, for example, only one man was left out of the original 40. On the home front, however, the population was not told the truth, with newspaper headlines announcing “Kitchener’s Boys—New Armies Make Good,” or “Great Day on the Somme.” But these same newspapers also began publishing the lists of the killed, missing, and wounded. The public was stunned and horrified, especially those towns that had raised “Chums” or “Pals” battalions.

The attacks pressed on. Haig, obviously misinformed, stated that the German Army “has undoubtedly been severely shaken and he has few reserves in hand,” even as the Germans were bringing up reserves. One reason for this confusion is that generals and their staffs simply did not know what was going on at the front. Once attacking troops left their trenches, they advanced into the foggy unknown; only with the invention of the walkie-talkie would this black hole be removed. Runners or carrier pigeons brought back scattered, isolated reports of conditions at the front for overworked staffs to try to piece together, but command and control was virtually impossible.

There were other factors at play, too. One was Haig’s bulldog-like obstinacy and confounding optimism. This was his first great offensive as C-in-C and for political reasons he wanted battlefield success. The cost of these whims was high: During the battle’s first three days the average divisional casualties were 3,320 men; two weeks later the British Army was suffering 10,000 casualties a week with a daily average throughout the entire offensive of 2,500 men.

On the German side, Falkenhayn had been surprised at the magnitude of the British attack, which gradually pulled his attention away from his bleeding-white operation at Verdun. Despite the slaughter on the 1st, the German line had indeed been shaken in places and only hesitation and a lack of information and coordination on the part of British forces prevented a serious collapse and allowed time for the line to be reinforced. After sacking the Chief of Staff of the battered Second Army, Falkenhayn put in his own man, Colonel Friedrich Karl von Lossberg, who promptly reorganized the German forces. No longer did they heavily man their first line of trenches; now the ruined systems and shell holes were filled with thinner forces, letting the British infantry sweep forward and then knocking them back with counterattacks by reserves from the support lines. It was an effectively fluid tactic that blocked Haig’s desire for a decisive breakthrough. Falkenhayn also ordered that every inch of lost ground be retaken, and he started pulling divisions and guns from Verdun to shore up the line on the Somme.

“Well, They Were Mown Down, Just the Same as What We Were”

On July 2, British forces struck at La Boiselle and Ovillers, which they failed to take, although a German counterattack at Montauban was repulsed. Once again, it was the French who prevailed, breaking through the line south of the Somme and rounding up 4,000 prisoners by July 4. The battle was now becoming one of hellish fights over little villages and small woods, soon reduced to charred, jagged stumps. La Boiselle fell on the 6th and most of Trônes Wood was occupied on the 8th, until the British were driven out. Now it was the Germans who were charging across open fields, with predictable results. Corporal W. Shaw of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers related that when the Germans were attacking “well, they were mown down, just the same as what we were, and yet they were urged on by their officers just the same as our officers were urging us on.… Our machine-gunners had a what of a time with those Lewis machine-guns. You just couldn’t miss them.” After a week and a half of fighting, the Allies had forced the Germans back one to two miles. By the middle of July, Mametz had been secured by the British, and the tally of German prisoners stood at 7,000. Although Haig wanted to strike again on his right, he was now under pressure from Joffre and Foch to take Pozières ridge, with Joffre even ordering Haig to obey. Heatedly, Haig told him that he was ultimately responsible to the British government.

On July 2, British forces struck at La Boiselle and Ovillers, which they failed to take, although a German counterattack at Montauban was repulsed. Once again, it was the French who prevailed, breaking through the line south of the Somme and rounding up 4,000 prisoners by July 4. The battle was now becoming one of hellish fights over little villages and small woods, soon reduced to charred, jagged stumps. La Boiselle fell on the 6th and most of Trônes Wood was occupied on the 8th, until the British were driven out. Now it was the Germans who were charging across open fields, with predictable results. Corporal W. Shaw of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers related that when the Germans were attacking “well, they were mown down, just the same as what we were, and yet they were urged on by their officers just the same as our officers were urging us on.… Our machine-gunners had a what of a time with those Lewis machine-guns. You just couldn’t miss them.” After a week and a half of fighting, the Allies had forced the Germans back one to two miles. By the middle of July, Mametz had been secured by the British, and the tally of German prisoners stood at 7,000. Although Haig wanted to strike again on his right, he was now under pressure from Joffre and Foch to take Pozières ridge, with Joffre even ordering Haig to obey. Heatedly, Haig told him that he was ultimately responsible to the British government.

Meanwhile, Rawlinson had rediscovered a basic principle of warfare: the surprise attack. He planned to smash through the German line between Delville Wood and Bazentin-le-Petit, sweeping up the strategically important Trônes Wood along the way. Over Haig’s vigorous opposition, Rawlinson’s scheme involved moving the troops up under the cover of night and, following a short, massive bombardment, attacking at dawn. The British struck at 3:30 in the morning on July 14 after hurricane shelling, overrunning the German first and second lines and beyond to the outskirts of High Wood—one of the Somme’s dominant rises—and Delville Wood. In this tangled, burned-out forest, the South African Brigade became involved in some of the bloodiest fighting of the war. They called this spot Devil Wood.

This was the turning point of the Battle of the Somme, as the German line buckled. Two squadrons of cavalry from the 7th Division were even moved up—the first time soldiers on horseback had fought since the beginning of the war—and the flicker of a breakthrough appeared. As the British cleared High Wood, though, the impetus of their attacks waned, giving the Germans time to rush in reinforcements who counterattacked with vigor, forcing the British to withdraw the next day. It had been a close call, but now this position would not fall to British troops for another two months. The Somme, like Verdun, had transformed into a huge meat grinder, chewing up men for little gain. Haig’s grandiose vision of a breakthrough had degenerated into a war of attrition. By the end of July, the British and French had lost 200,000 men, the Germans 180,000, for gains of about three miles. Despite this evidence, Haig remained sanguine. “In another six weeks,” he claimed, “the enemy should be hard put to find men. The maintenance of a steady offensive pressure will result eventually in his complete overthrow.”

History’s First War Documentary

With the wounded filling London hospitals and the newspapers publishing unending casualty lists, Haig received a confidential letter from his friend, Chief of the Imperial General Staff, General Sir William Robertson, warning him that “the powers-that-be are beginning to get a little uneasy in regard to the situation. The casualties are mounting up and they were wondering whether we are likely to get a proper return for them.” Haig was feeling the heat from the dynamic and powerful Welsh populist politician Secretary of State for War David Lloyd George, who mistrusted and thought little of generals. Lloyd George expected results from such losses.

A month and a half after the start of the campaign, history’s first war documentary opened to packed London cinemas. The Battle of the Somme, filmed sometimes directly in the lines by J.B. McDowell and Geoffrey Malins, brought the war home for the first time to British civilians. Although designed more or less as a morale booster, its realistic scenes—some apparently staged by actors—enthralled and shocked moviegoers even as it stripped their naiveté away. During one showing a woman screamed out, “Oh God, they’re dead!” The government propaganda machine could not explain away these images. When the film ended its run in the fall, around 20 million people had seen it, forever exposed to the grime and death of modern warfare.

The fall rains were now approaching. Haig decided to throw in his trump card, a secret, potentially war-winning innovation: the tank. Although manned by novice crews and still plagued with mechanical troubles, 36 Mark I tanks—some armed with 6-pounder guns, others bristling with machine guns—were detailed to assault the German lines at the villages of Flers-Courcelette. Writing to Robertson on August 29, Haig confided, “I hope the Tanks prove successful. It is rather a desperate innovation.” Lumbering up to enemy positions at three miles per hour on September 15, 18 tanks (the rest had been ditched due to mechanical problems) terrified the Germans, hundreds of whom fled, surrendered, or were killed by fire from the tanks and their supporting infantry. It was one of the least costly victories of the war, even though Haig had tossed away a great tactical surprise for an insignificant gain. Again, it could not be exploited and there was no breakthrough.

At the end of August Falkenhayn, out of favor with the Kaiser because of lack of success at Verdun and the losses in men at the Somme, was replaced as chief of staff by Field Marshall Paul von Hindenburg, who brought along his deputy from the eastern campaigns, Erich von Ludendorff. Unbeknownst to the German High Command, Haig was also feeling a sense of urgency. Under constant pressure from Joffre to maintain the offensive, and with another important Allied strategic conference coming up at Chantilly, Haig wanted some kind of victory to strengthen his hand both for the negotiations with the French and his own political leaders. Indeed, in a meeting with Lloyd George, Haig was told that another Somme-like offensive in 1917 was unacceptable. The Secretary of State for War had his sights on other fronts, notably against the Ottoman Empire.

A Historical Battle of ‘Firsts’

As the rains were turning the cratered Somme battlefields into a turgid sucking muck, the British launched a final attack against Beaumont Hamel and other villages astride the River Ancre, locations they had been attempting to conquer since the beginning of the offensive. En route to Chantilly, a relieved Haig was informed that Beaumont Hamel had fallen. At last he could confront the French and the politicians with a victory of sorts. By now the first snowfall had dusted the Somme battlefields and once again a white mist obscured both the living and the dead. On November 18, Haig called off the offensive.

It had been a momentous battle—or series of battles—that stands out in history because of its many firsts: the tank, the war documentary, the first test of the New Armies. For the British, there was another bloody first—the enormous casualties. They had lost 419,654 killed and wounded, the French 204,253; the German figures varied between 450,00 and 600,000. In 130 days of fighting 31,000 Germans had been taken prisoner and 125 guns captured; this sounds impressive only if one does not compare it to more successful attacks. At the Battle of Arras, for instance, 13,000 Germans and 200 guns were taken on the first day alone. More depressingly, the maximum line of advance, after nearly four months of hard fighting, was at Les Boeufs, seven miles into German-held territory.

The blood spilled at the Somme stained Haig’s reputation. His callous indifference to the suffering of his men ensured that he would be despised by most of them and their families. Later, apologists for Haig would protest that he was forced into this battle to save the French at Verdun. However, not only did the French Army participate magnificently at the Somme, outperforming the British, but they continued battling at Verdun until December 18, long after Haig had called off his attacks. Just as spurious is Haig’s claim that he had never planned a breakthrough and only wanted to wear down the German reserves. But the battle’s repercussions went beyond him. By the end of the year, British Prime Minister Herbert Asquith’s coalition government, haunted by failures on the Somme and elsewhere, fell and Lloyd George came to power in Britain.

The Battle of the Somme has generated many myths and clichés, of “stupid” generals, inflated German casualty figures, the primacy of the machine gun over artillery. An enduring myth is that the British soldier with his 66-pound pack was so encumbered he could barely move, let alone fight. But with the modern American soldier in the recent Iraqi war lugging around 100 pounds of equipment, this would appear to be an overstatement.

A”: a Byword for a Bloody, Protracted, and Senseless Massacre

The Somme was a Great War battle par excellence. It quickly disintegrated into a series of small, vicious mini-actions for a few yards of shattered earth. It was presided over by generals sublimely convinced of their own abilities and battle plans, confident of victory and unconcerned by the agony of their men, arrogant in the racial superiority of their nations, closely watched over by equally strong-willed, self-confident politicians at home, unafraid of meddling and questioning their commanders’ decisions. And the whole messy thing was observed with cynicism by Fritz or Tommy or some poilu from the mire, stink, and death of the front lines. Later, a large number of these common soldiers—the product of fine 19th- century schooling—would write brilliant, poignant, brutally realistic books about their experiences, a unique literature that would forever alter how later generations view warfare.

The Somme was a Great War battle par excellence. It quickly disintegrated into a series of small, vicious mini-actions for a few yards of shattered earth. It was presided over by generals sublimely convinced of their own abilities and battle plans, confident of victory and unconcerned by the agony of their men, arrogant in the racial superiority of their nations, closely watched over by equally strong-willed, self-confident politicians at home, unafraid of meddling and questioning their commanders’ decisions. And the whole messy thing was observed with cynicism by Fritz or Tommy or some poilu from the mire, stink, and death of the front lines. Later, a large number of these common soldiers—the product of fine 19th- century schooling—would write brilliant, poignant, brutally realistic books about their experiences, a unique literature that would forever alter how later generations view warfare.

Among the hundreds of thousands who fought at the Somme were some extraordinary men, and the horror of that battle would taint their minds and determine their future actions. British poets Graves, Blunden, Sassoon, and Rosenberg all went through it; Graves himself had been hit in the chest and left to die, but survived to write a masterful memoir of this time, Goodbye to All That. The American poet Alan Seeger, serving with the French Foreign Legion, was killed on the second day of the battle. His poem “Rendezvous” and its evocative opening line, “I have a rendezvous with Death,” is one of the most famous of World War I, or any war. Raymond Asquith, son of British Prime Minister Lord Asquith, was killed there. His death crushed his father, who thereafter lost the vigor to pursue the war. Harold Macmillan, British prime minister from 1957 to 1963, was severely wounded in the face by a grenade blast at the Somme. But perhaps the most famous soldier to fight in the battle was a skinny German corporal with a broad Kaiser Wilhelm mustache, Adolf Hitler. A brave and decorated dispatch runner, he was hit in the face by a piece of a shell that had slammed into his dugout, killing those around him while ironically sparing the future conqueror of Europe.

Verdun was ghoulish, Kaiserschlacht vast and breathtaking, but the Somme—or rather the first day of the battle—lingers in memory as an intensely sad affair, a monumental loss of innocence not only for the British Army, but for Britain itself, and the world. Those tragic, cheering ranks of “Pal” and “Chums” battalions hurled into eternity with the fluid sweep of the machine gun cannot be forgotten. Entire firms, neighborhoods, and villages had suddenly lost all their young men. At the time, the impact of this was profound, especially as loved ones compared the immensely long casualty lists with official pap. A whole generation had been extinguished, an immense loss that is still felt today, and lies like a black dream deep within the psyche of the British nation. This trauma was a factor in transforming the sociopolitical landscape of postwar Britain. On the grassy expanses of the Somme, notions of war as a chivalric adventure died. Concepts of obedience and an unquestioning belief in one’s leaders vanished. Indeed, “the Somme” has become a byword for a bloody, protracted, and senseless massacre. The antiwar, anti-authority revolts of youths from the summer of 1968 have their roots in the bitter experiences of the youths killed in the summer of 1916.

Today, the Somme’s undulating slopes and ravines have been reclaimed by farmers, but it remains a place of pilgrimage for the young and old of Britain, Canada, Australia, South Africa, and Germany who pick their way across its expanses in hushed and awed reverence. The battle has left a haunting image, in the written word, in film, but most profoundly in the thousands of pale white gravestones dotting this scared patch of France.